Biographers can report what happened to their subject and when; they can also suggest reasons why it happened. But only a novelist can climb inside the subject’s head and describe their deepest thoughts and insecurities. It’s in that secret place, hidden behind the bare facts of a life, that I like to write.

Gill Paul writes for Female First

I’m not alone in writing fiction about real characters: Hilary Mantel, Philippa Gregory, Joyce Carol Oates, Robert Graves, Paula McLain and Jeffrey Archer are just a few of the novelists who have chosen this route. None of them was attempting to rewrite history – it is always clear they are writing fiction – but they wanted to go deeper than the history books allow.

The best novels about real people make us re-evaluate the subject and perhaps alter our preconceived ideas. Cromwell, for example, is softer and more human in Wolf Hall than he is usually portrayed. I tried to do this with Wallis Simpson in Another Woman’s Husband. It seems to me she’s had a bad press from biographers who focused on her alleged affairs, and rumours that she possessed special sexual techniques (for which there is no evidence). I tried to illustrate her vulnerabilities and explain what made her the woman she became by using a trope many novelists have used before me: I viewed her through the eyes of her lesser-known best friend. Mary Kirk met Wallis at summer camp when they were both fifteen and remained her friend right up to the abdication crisis, so she had a unique viewpoint. History has judged Wallis for the effect she had on the British monarchy; I judged her for the way she treated her schoolfriend.

There are loads of dangers and pitfalls for novelists writing about real people, especially if their story is already well known. When you are attributing made-up thoughts and dialogue, perhaps adding a few tics and quirks, there will always be some who object: “He/she would never have done that.” I’m sure Joyce Carol Oates got a few such letters when she dared to write her brilliant novel Blonde, about Marilyn Monroe.

Do you need to tell the truth in novels about real people? I don’t think so. Personally, I try to stick closely to the historical facts, not because I feel an obligation to do so, but because I am curious to reach a version of the character that feels true. I will omit facts that don’t contribute to the story I am telling and might play around with the timeline, but I always include a historical afterword where I confess what was made-up. But if a novelist chose to reinvent someone entirely – for example, making Abraham Lincoln a vampire – that could also make a good novel.

It is especially tricky when you write about someone within living memory. I did this in The Affair, which takes place during the making of Cleopatra in Rome in 1962, when Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton fell in love. Both of them were long dead by the time it was published, but I was flabbergasted when I got an email from the wife of the director, Joe Mankiewicz, because I had covered the story of the beginning of her relationship with Joe in the novel. Fortunately she approved! You can’t libel the dead, but you need to be super-careful about the living.

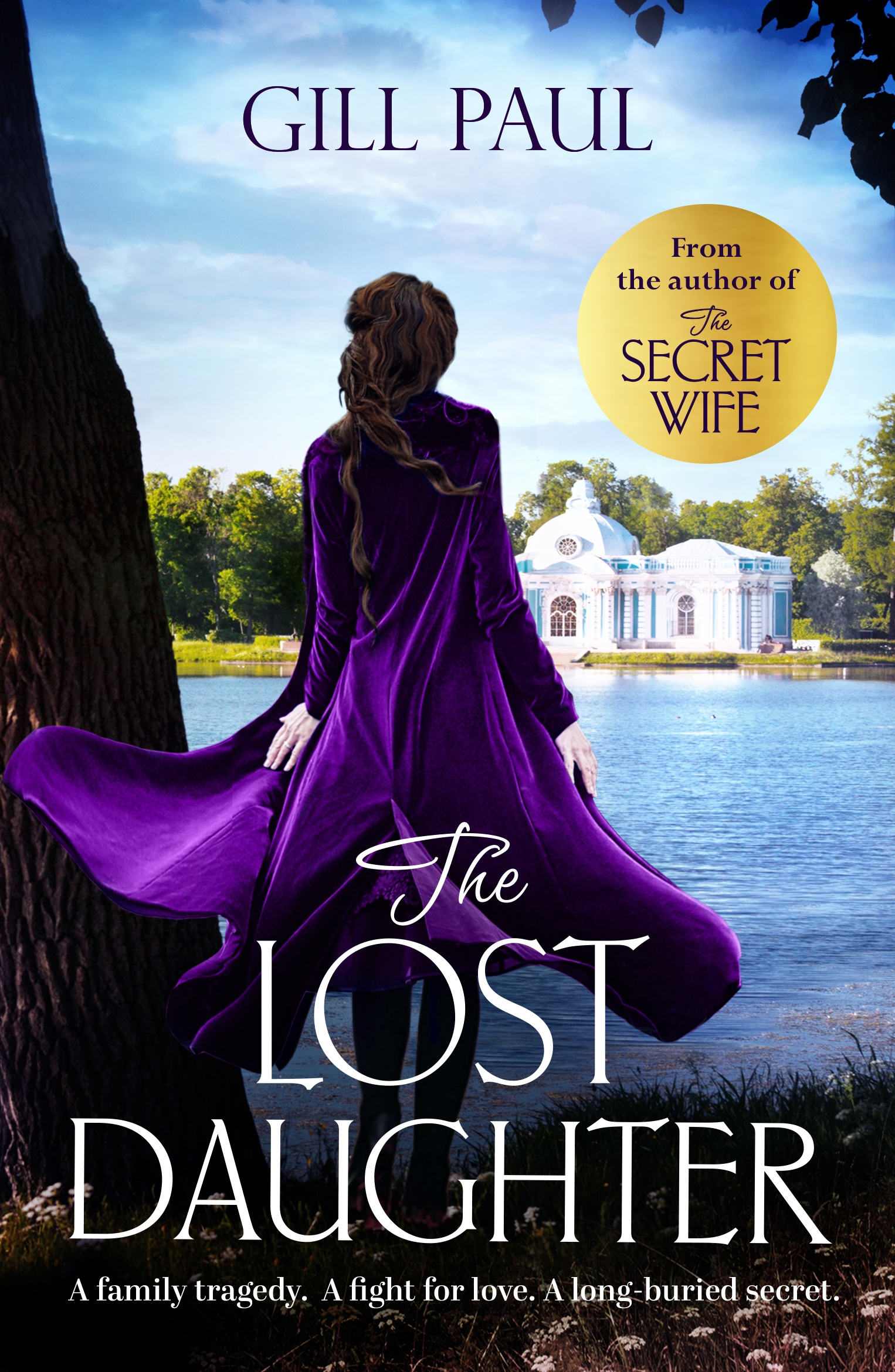

How do you step into the shoes of a historical character? First of all, I go back to primary sources: their letters and diaries, if they left any. In my latest novel, The Lost Daughter, I write from the point of view of Maria Romanova, middle child of Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia. Her letters don’t give much away but memoirs by the family’s tutors are more productive, and the hundreds of photographs and home movies the family shot (available online) are revealing.

I had to be careful not to view Maria from a 21st-century perspective. One of the most important things about the Romanovs was their devotion to the Orthodox religion; another was their love of the mother country, which may have stopped them trying to escape the fate that awaited them. Since I am neither Russian nor Orthodox, this required a leap of imagination.

When writing about real people, I always hope I’ve done them justice – but that’s not the primary objective. The main obligation of the historical novelist is to write an entertaining novel that readers want to read. Apart from that, and the libel laws, there are no other hard-and-fast ‘rules’.

Gill Paul’s novel The Lost Daughter is out now in eBook and paperback, published by Headline and available on Amazon. RRP £8.99.