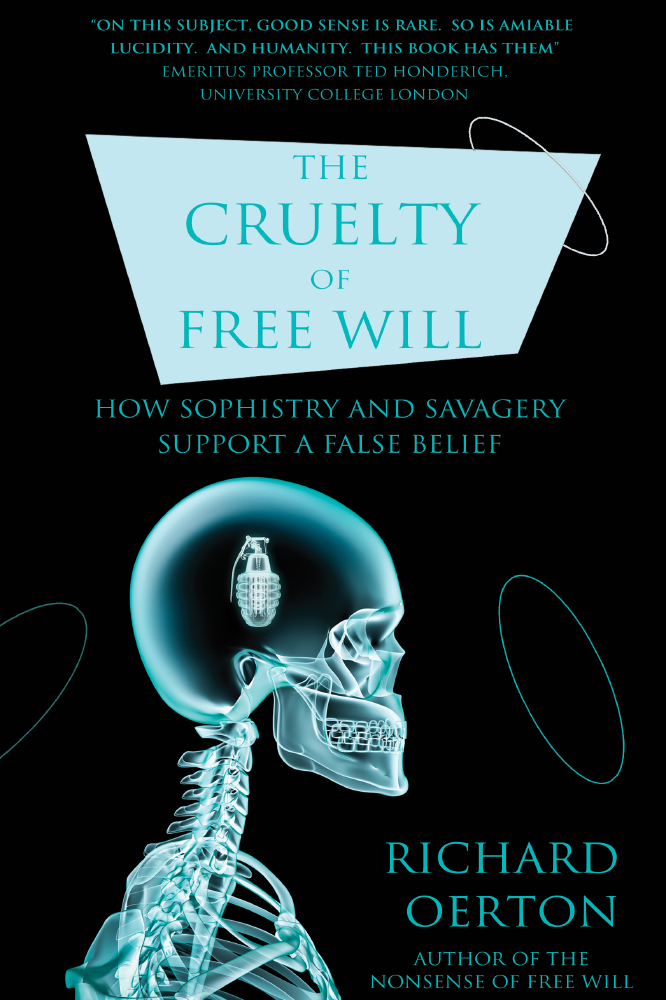

I've produced two books about free will and determinism. The Nonsense of Free Will appeared in 2012 and this year it was joined by a sequel called The Cruelty of Free Will. Both are aimed at the general reader.

Richard Oerton

There's nothing wrong with determinism. People usually see determinism as a Bad Thing: if our lives are 'determined', then surely we have no choices and we're reduced to the status of helpless cogs in an inexorable machine? But to be a determinist is simply to recognise that natural laws, laws of cause and effect, apply to human beings as they do to everything else. We come into the world with inborn (biological) characteristics; those characteristics then interact, as we grow up, with the environment in which we find ourselves; and at any given moment in our lives we are the products of this process of causality. We make our own choices, but we make them in the way we do because we are the people we are. Wouldn't it be alarming if that were not so?

There's everything wrong with free will. But to believe in 'free will' you must believe that it is not so - that in any given situation we really might behave in a way different from the one in which we do behave. You must believe that if there were two atom-for-atom identical people, each in an identical situation, one might behave in one way and the other in another. This is the idea of free will which people have: you could call it 'free choice'. But it doesn't stand up. We choose to behave as we do because of the motivations (within our characters, our brains) that causality has given us. Free will, if it existed, would sever the connection between our motivations and our behaviour, between what we are and what we do: we should have to be free from ourselves. This is a glimpse of insanity - or of magic.

And quantum mechanics makes no difference. The laws of cause and effect don't appear to apply to sub-atomic particles. But this doesn't leave room for 'free will' because even if the indeterminism of these particles could affect human behaviour (and it seems clear that it couldn't), that would serve only to make it random, and randomness isn't free will.

Belief in free will involve hypocrisy. The sciences that seek explanations for human behaviour assume that determinism (or causality) is true: otherwise there could be no explanations. And we make the same assumption every day when we try to understand why particular people have acted as they have. Free will never comes into the picture… but we still keep our belief in it safely tucked away in a separate compartment of our minds, ready for use when needed.

And it sometimes involves conjuring. A few philosophers (called 'compatibilists') say that although determinism is true, we still have free will. But their free will isn't our free will. It doesn't involve any freedom of choice and they're reduced to claiming (for example) that better education gives us more 'free will'. The philosopher Kant called compatibilism 'a wretched subterfuge'.

And it's a bit like religious belief. Today free will goes largely unquestioned and unexamined: it's a matter of almost universal faith, like religion in times gone by. But there's a difference: God is by definition supernatural - literally, above all natural laws - so his existence can't be proved or disproved, but free will isn't like that. Its existence should be capable of rational justification, and it isn't.

Free will belief isn't just mistaken: it's harmful. Free will belief reverberates all through our social and moral attitudes and institutions, and it skews them in such a way as to produce cruelty and injustice. It's thought to justify all the hatred, contempt, vengeance and retribution which we heap on people who do wrong. But what determinism tells us is that these people are built to do wrong, and it must follow that they do not deserve these things. Of course we have to take action against criminals, locking up the dangerous ones and trying to reform them all, but punishment as retribution can't be justified. Their acts result from biological and environmental luck, not from self-created 'wickedness', and if we had had exactly the same luck we should be exactly the same as them.

The idea of free will is used to justify the unjustifiable. Those most keen to uphold the idea of free will are those who live comfortably within the present social and moral 'dispensation' and want to preserve it. Their belief allows them to dismiss and denigrate those whose lives are bleak (because they could perfectly well change them by an act of 'free will') and to admire the rich and powerful (because they have done just that). All positions in life are thus somehow 'deserved' - a comforting thought indeed.

We cling to the idea of free will because we're still a savage species. You won't have liked some of my earlier assertions and you certainly won't like this one - but surely it's true. Evolution has not (yet) produced in us a species dedicated to the general welfare of its own members or with any strong inhibitions against killing, harming or exploiting them. (If you doubt this, pick up a newspaper.) We are still a savage species, and free will belief lets some of it out of the cage in which, most of the time, civilisation confines it.

Rejecting 'free will' doesn't have to change your life. But there's an important distinction between reason and emotion. Acceptance of the case against free will is not going to sweep away the emotional foundations, which underpin our lives. A rather eminent lawyer who read my second book said that she was intellectually convinced by it but couldn't accept it emotionally. I get that: many would feel the same. But even emotional attitudes can change over time and we may find that this one changes gradually - if our savagery doesn't destroy us first.