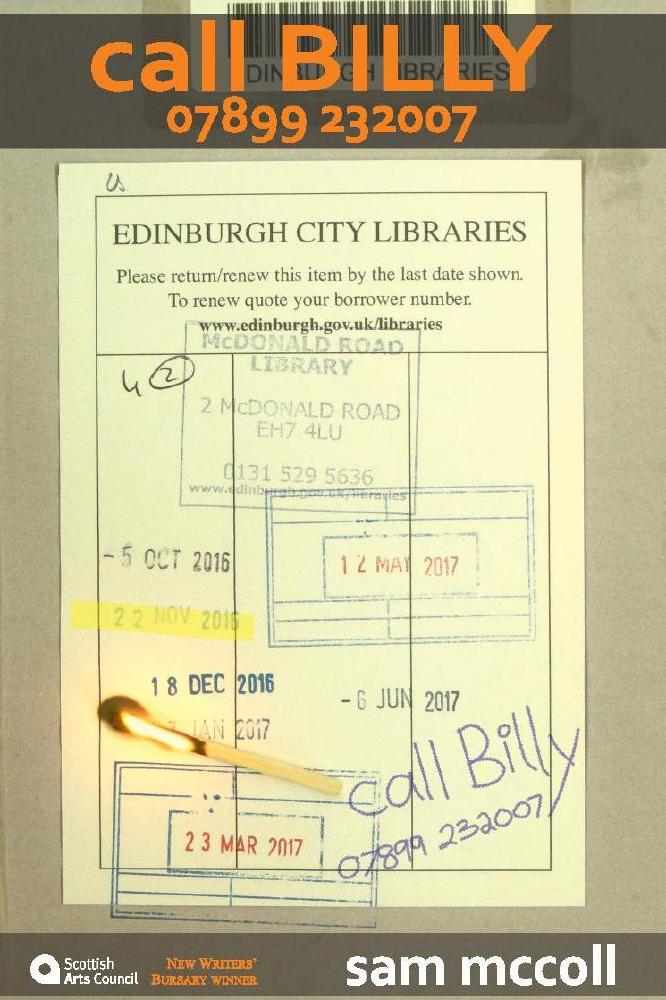

I’m often asked about the building of character in Call Billy (and btw, do please call him – now he’s what you call dysfunctional…).

Call Billy

Are they modelled on real people – people I know? I have to say, no. No-ish. There are good reasons for this. I grew up in a family hushed by violence. I was orphaned at twelve, none of it was easy. I have strong opinions and reactions to the people who shaped me. When I find myself slipping under their skin, rather than into the mind of the character in my novel, I lose what I believe is essential objectivity, and as a consequence I risk blurring both my boundaries and my judgement.

So who holds the pen? How, if at all, does my bewildering past help me as a writer? I see myself as a lucky survivor. Despite many seeming advantages, I spent much of my adult life recreating the dismal ethos of my childhood. And then, something (fear most likely) made me look up, make that phone call, get help. Changing oneself, rather than someone else is a never ending process and it changed everything for me. Still does. I am my past, sure, but if I see a room full of friendly faces as a threat (as they once were), and react with a flight or fight response when I’m about to do a reading, well, I’ll not get a return invite, let’s put it that way.

But can corrosive, life – crushing instincts help my writing? Sure they can. Nearing the end of my first year in therapy, my counsellor said, ‘Now you no longer need to know how everyone around you is feeling, in order to stay safe, you’ll need to find another use for your considerable analytical skills.’ So I did. I consciously rooted out almost all my childish coping strategies over the years and replaced them with more helpful life-affirming skillsets. But did they vanish? Hell no. I packed them tidily away in the natty, well painted, Ikea storage unit in my mind, where I could keep a beady eye on them. I’m a tidy person, I can’t settle down in a mess. This means I’m often dusting them down, checking them for moth or escapees, and thoroughly enjoying the freedom their confinement allows me. In other words, I have access to them, and when I need them to set fire to my writing, I trot them out for a bit of exercise.

So yes, in a controlled way, the experience of my past adds hugely to the authenticity of my writing. But controlled is the word. Because, in my experience, to write a good story, I need to be as balanced and considered and dispassionate and reflective as is possible for me to be.

My husband says with unnerving confidence that he’ll put the word ‘Tenacity’ on my grave. Granted, he is a lot younger than me, but still, I do a lot more yoga, and cycling for that matter. But fair’s fair, he’s right – I am. Against all the apparent evidence to the contrary, as a child, I stubbornly believed in happy endings, in my happy ending. That was tenacious. And so it goes on. If I wasn’t tenacious, I wouldn’t deconstruct a sentence thirty of forty times before finally slinging it out. I’m pretty sure there wouldn’t be a story if I wasn’t tenacious. Having said all that, I often toy with the idea of banishing tenacity to the wardrobe, to be stored between or alongside ‘suspicion’ and ‘mistrust’, because then I might get out more, spend more time with the family, and plant a lot more trees. Now that may be something worth putting pen to paper for.

On the other hand, as Tenacity is still running amok with my emotions, it’ll have to be all my own work. Ugh.