I was sitting by the pool of The Foreigners’ Club in Jakarta reading a novel. The waiter, an elderly man dressed in black trousers and white shirt, arrived silently at my side and arranged the ice bucket, with three bottles of Indonesian beer protruding invitingly from it, on the low table beneath my parasol. ‘Bintang Bapak?’ he asked, referring to me deferentially as ‘father,’ though he was older than my dad. The fourth bottle fizzed into life as he prised it open; he poured it expertly into the chilled glass. I gulped the cool, foamy beer as I surveyed my surroundings. Here was I, a policeman, counter terrorism attaché to the British Embassy, treated like a king, whilst beyond the walls of the club the impoverished throngs of Jakarta went about their relentless humdrum lives. A pang of distress accompanied the tang of beer and I buried my head in my novel.

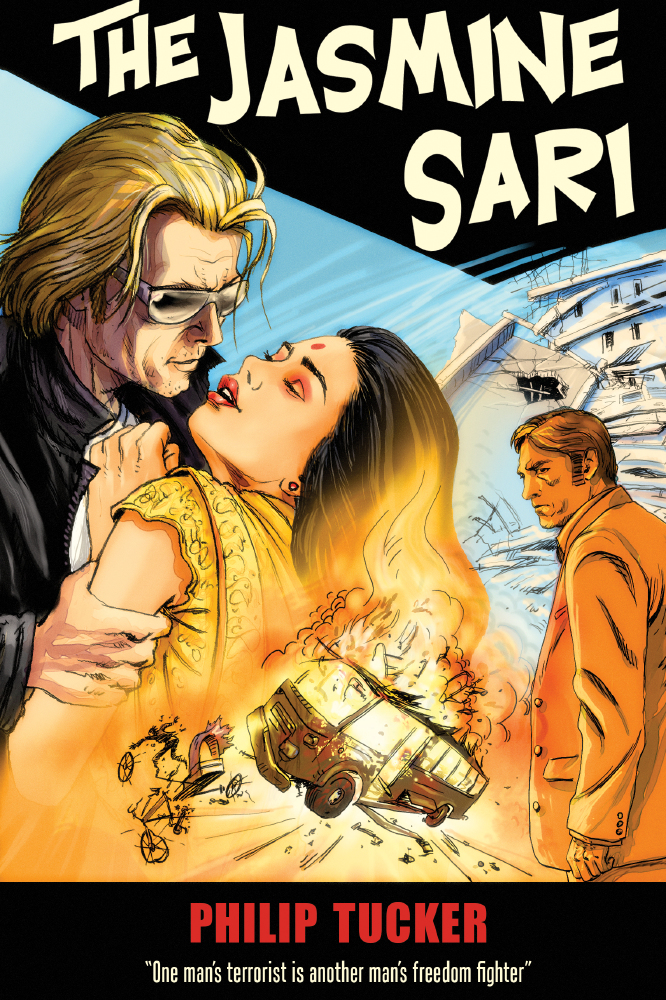

Philip Tucker

The book offered me no succour. I was reading Burmese Days, set in and around the exclusive European Club during the Raj and written by a slightly more famous British police officer serving his country overseas - George Orwell. I could not help but be struck by the similarities between my situation and the one Orwell had himself faced and had fictionalised. Though in my case locals were not barred from membership of the foreigners’ club as they had been in Orwell’s time in Burma, very few actually joined and those that did were very wealthy. A member rarely came across an Indonesian sitting around the pool, save for the lifeguard and the kids’ swimming instructor. Now I felt a waft of inspiration – here was the setting for a novel of Orwellian proportion!

But Orwell’s influence went beyond encouraging me to use the luxurious club as a mere backdrop. He was a man of letters, of substance. He would not have been satisfied with serving up the usual fare of cops-turned-authors: police procedurals, whodunits or a collection of amusing little experiential ditties. Orwell wanted to write on the bigger themes, to put forth his views on the politics of policing in someone else’s country. He was self aware enough to see himself as the locals saw him: an instrument of Empire, an unwelcome enforcer of an invader’s laws. In Burmese Days, Orwell wrote about the hypocrisy and fragility of the colonialism within which his intensely human story of personal relationships took place. And if Orwell the copper could do that, surely Tucker the copper could have a go?

As a police officer and student of terrorism, I am most interested in what makes an ordinary person a terrorist. When we’re all angry about world events, what process occurs in a particular individual to make them justify the use of violence against innocent people, when the rest of us find more peaceful ways to protest? This process of radicalisation, a journey towards justifying and using violence to achieve a political end, was to become my bigger theme, the one that I explore in The Jasmine Sari. It’s the area of policing and of politics that inspired me to write the story that I did. Because radicalisation is not just an issue for law enforcement, it’s a political topic; one’s view on whether a person has been radicalised is informed by the political context in which the observer sits. George Orwell himself went to Spain in 1936 to fight against fascism, yet he is never referred to as having been radicalised, he simply made a personal choice to try to help Spain secure her freedom. And how did Franco view these foreign fighters; how would he have viewed Orwell - the policeman turned writer turned political activist? Not as a freedom fighter, that’s for sure.

This, then, is the bigger theme explored in The Jasmine Sari. It’s ultimately a novel, a personal story about a copper in Bangladesh, inspired by a comparison between my own experiences as a police officer and those of Orwell. But the dilemma at the heart of the book is inspired by reflections on Orwell’s role in Catalonia: how to tell the good from the bad. After all, one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.