Steve McQueen’s new film Widows will blow most of you away. The film, based on the classic 1980s Lynda La Plante novel, features a group of gangster widows who turn to crime to finish the epic heist their husbands started.

AJ Waines writes for Female First

It’s a great film but for me, rather than offering the pure escapism of a classic popcorn movie, it actually took me back to a more serious place. A place where I heard some of the darkest stories I have ever heard and inspired my second career as a crime thriller writer.

Ten years ago I wasn’t a novelist. I was a psychotherapist working with female criminals and ex-convicts in Broadmoor. Offering an ear and place for them to discuss life outside and what they would do on their return, I spent hours with these women. Now, the women in Widows are sassy and wonderfully scripted, but of course real life is not as straight forward. Its often more complicated to reach an individual. They don’t come from a world where measured, frank talking, particularly about emotions or a life ‘going straight’ is on the agenda for conversation.

So when words don’t come easy, we had to use some new methods. In my work as a psychotherapist, I’ve been fascinated and frankly astounded by the results when using any form of art therapy: drawings, sketches or even exploring emotions using metaphors (imagework). It’s a very gentle way for an individual to feel their way into a dark and complex emotional world and is incredibly effective in helping them explore their inner selves.

Imagework refers to exploring shapes and pictures in one’s minds-eye, especially helpful when a patient is trying to describe abstract concepts such as depression and anxiety. One of the ex-convicts I worked with, Louise, was missing meals at the safe-house I used to visit, becoming more and more withdrawn and uncommunicative. The support team were worried she might self-harm again or could even return to offending: she had a record of punching victims so violently that on one occasion she broke a woman’s neck. On that visit, all Louise would say was that she felt ‘crap’ and we couldn’t seem to get any further than that.

I asked Louise if we could try something, like a kind of game. She’d been looking glum, watching kids’ cartoons on TV. Following on from that theme, I asked her if she could picture herself as an animal in that moment, and which one it would be. She said ‘a shark’ and showed me her teeth. I hung on in there and when we explored the image further, Louise said she felt she was being hunted, cornered and that at any moment, she was going to feel a spear in her back. Staying with the image, I gently encouraged her to tell me what the worst aspect of being the shark was and what it needed. I asked when she had become the shark and what was next for it, deep down in the ocean. Our exploration took an incredible turn and in the end, Louise was talking non-stop about wanting to have a child, but knowing social services would take it away from her. Suddenly, we had a concrete situation all the team could try to help her with, far more helpful than simply knowing she felt ‘crap.’

Instead of using our logical left-brain, image-work takes us into our right brain where we process creativity, intuition and imagination. This part of the brain also helps to get in touch with the subconscious more easily: I often found in my work that patients discovered feelings they didn’t know anything about on a conscious level! It’s great for people who find words difficult, who can’t express themselves well or for those who find it hard to talk to someone eyeballing them head on. When you focus on a drawing in front of you, it takes the pressure off ‘communicating’. It’s also good for people who hide behind words, the ones who can talk themselves out of a paper bag, but rarely let themselves really be seen!

I would introduce the idea of using pencils and crayons to virtually all my long-term clients, explaining that they did not need to be able to draw and that stick figures or blobs would work perfectly well. I found drawing particularly useful for victims of trauma. For those who couldn’t find the right words to express how they felt or bring themselves to say something devastating out loud.

To give you an example, Mark had what he described as a ‘difficult’ relationship with his mother. He kept getting side-tracked as we spoke, so I asked him to draw himself on a sheet of blank paper, then find another image for his mother. He drew a tiny stick person for himself and a huge brick on top of him to represent his mother! That said a lot! Mark was as surprised as I was, claiming he’d never thought of their relationship like that before. The look of triumph and relief on his face was remarkable. He’d conveyed something with this image that he would have spent a long time trying to explain to me. Here it was in a nut-shell and we were then able to work with the image itself to work towards change: Where would you like to put the brick in the picture? What would it be like to step out from under the brick? What would happen to the crushed figure if the brick was removed?

Mark tried sketching different images, all very basic, then stood back to see how he felt about the impact of each one. It gave us a new realm of choices and solutions to explore which were eventually mapped onto his actual situation. It was far more powerful than just ‘talking about’ his mother. In a short time, he was able to admit that she had sexually abused him as a child. When he came out from under the brick in the picture, he saw that the hardest aspect, hidden under the guilt and hatred he felt for her, was that if he confronted his mother, she would stop loving him. He felt stupid and ashamed about that. Within a few weeks Mark had sent a letter to her, explaining exactly what he felt. It was the first step in his recovery.

Words are often limited or clichéd when we express emotions, but there’s a different energy with drawing. I found it useful for exploring vague and supressed feelings. Shelly, who had been bereaved, continued to deny her anger at the deceased, until she saw she’d revealed it in the image she drew.

Drawing can also access the child element within us. No one needs to be artistic, in fact this can be distracting, as the focus becomes making the picture ‘look good’ instead of a direct form of expression. Drawings cut through lots of adult defences and masks. I’ve witnessed a patient make one small drawing and suddenly we’ve been in touch with a vulnerable part of them it might have taken weeks to reach through ordinary conversation.

(Names have been changed).

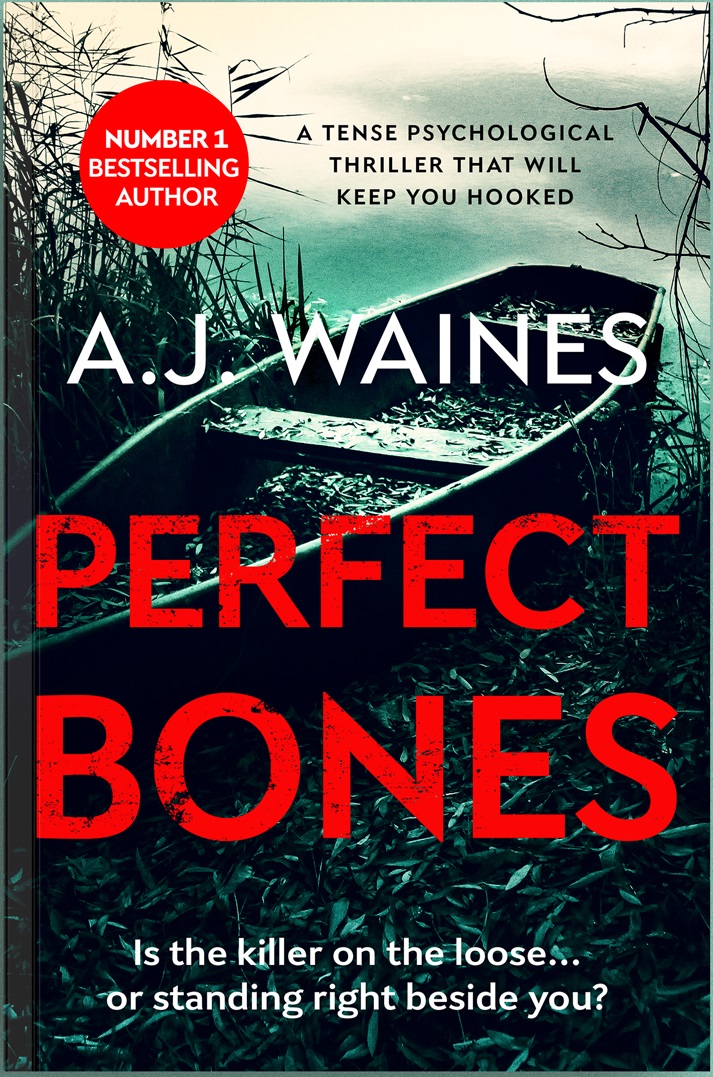

A.J. Waines' new book Perfect Bones is published by Bloodhound Books and is out now, RRP £8.99.