Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was a pioneer of photography, not just in her work with scientists such as Sir John Herschel on lenses and methods of developing prints, but also in her continuous experimentation in the creation of her art. Not satisfied with just reproducing nature in a photograph, Cameron wanted her images to ‘electrify you with delight and startle the world’, as she wrote to a friend in 1866. She smeared and scratched her negatives and played with focus to produce works of art that were both admired and derided in her lifetime. Here are five essential facts about this extraordinary woman:

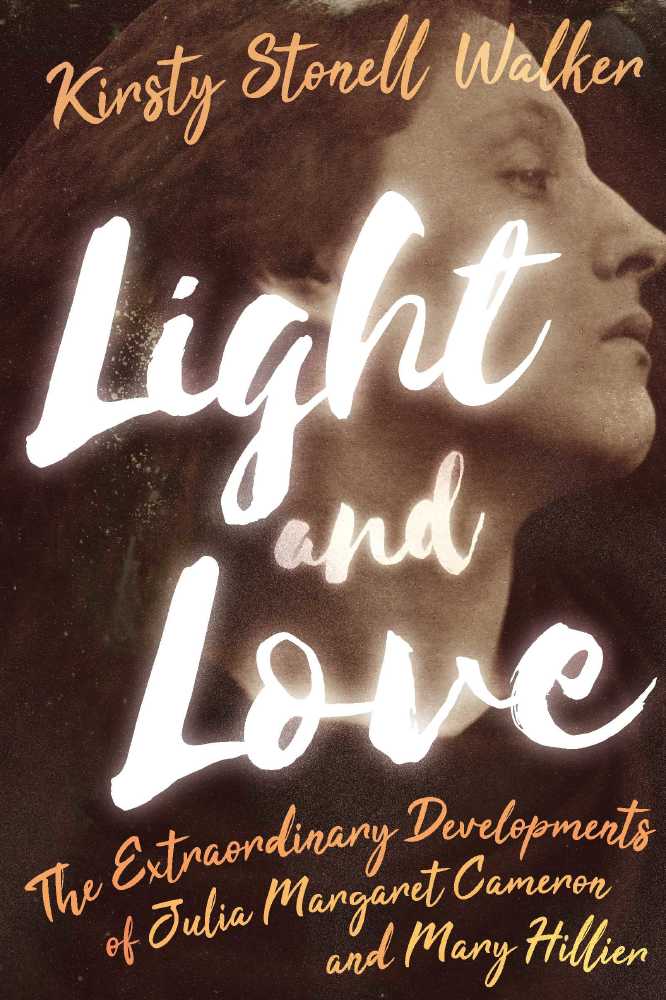

Light and Love

1. She was 48 when she was given her first camera as a present from her daughter, but she was already fully conversant in the practice of photography. Much has been made, not least by Cameron herself, of how this middle-aged woman was given a camera to keep her out of mischief, only to become a ground-breaking artist. Cameron’s daughter Juley apparently wrote “It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater” on the gift. The gift was no fluke; by that time Cameron had assisted her brother-in-law, Viscount Eastnor, with his photographs, on many occasions. She had also taken lessons from professional photographers David Wilkie and Oscar Rejlander, the latter coming to Freshwater in 1862 to photograph Cameron and her family, as well as her neighbour Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Although Cameron embraced the myth that she had first discovered photography in 1863, she had already spent 25 years slowly immersing herself in the art and science of it all.

2. Cameron lived next door to her best friend and muse, the poet laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Cameron met Tennyson through a mutual friend, poet Henry Taylor, when they were living in Tonbridge Wells. Cameron was undoubtedly attracted to older men and took scores of photographs of both Taylor and her husband with their long white beards soft and cloudlike. Whilst she took images of Tennyson as well, it was his poetry that inspired some of Cameron’s finest photographs, including her final cycle of images taken before she left England for Ceylon in 1875. The Tennyson family moved to Freshwater in 1853 and welcomed the Camerons to their home on many occasions, especially when Julia’s husband Charles was absent at his coffee plantation in Ceylon. The calm beauty of the village in the south west of the Isle of Wight inspired Cameron to buy two houses next to the Tennyson’s home, Farringford. In the garden of her new home, Dimbola Lodge, Cameron had a gate built so Tennyson could pay visits with ease.

3. Many of the beautiful women in her photographs were her housemaids, all called Mary, who had very different fates. Cameron once said she employed her housemaids for their beauty, and then celebrated it in her photographs. She found her first maid, Mary Ryan, begging on Putney Heath with her mother, both refugees from the Irish Famine. Cameron took responsibility for Ryan, training her to be a maid but also allowing the girl to sit in on lessons with the Cameron children’s tutor. Cameron took Ryan with her over to the Isle of Wight, where she also employed both Mary Kellaway and Mary Hillier, two young local girls. All three Marys appear in Cameron’s early images of beautiful women, playing the Virgin Mary, the May Queen and Shakespearean heroines. One photograph of Mary Ryan, Prospero and Miranda, caught the eye of a young civil servant, Henry Cotton, who asked Ryan to marry him. His subsequent work made him Lord Cotton and the former beggar became Lady Cotton, whose philanthropic work was celebrated. Mary Hillier married the gardener of the painter G F Watts, another friend of Cameron’s who had moved to Freshwater in search of inspiration. She named her daughter Julia, after Cameron and her son George Frederick, after her husband’s employer and lived out her long life within a mile of where she had been born. For Mary Kellaway, her fate was less settled. She moved from the island to marry twice, but then her mental health collapsed and she was confined to an hospital, diagnosed as ‘lunatic’ at the age of 51. She died shortly after being released as an old woman into the care of her family in 1913.

4. When a tragedy happened in her home, Cameron turned to her camera. After the death of their parents, sisters Mary and Adeline Clogstoun came to live with their great aunt Julia at Dimbola Lodge in Freshwater. They joined a boisterous household with Julia younger sons and her visiting grandchildren often playing in the spacious rooms between lessons from their governess. In June 1872, the governess was ill, leaving the Clogstoun sisters playing with Cameron’s granddaughter Beatrice. Despite being told to take care, the girls continued to jump on each other’s backs, and when Blanche jumped on Beatrice, already on Adeline’s back, ten-year-old Adeline’s spine was broken. The child was laid out in an upstairs room and died without regaining consciousness, devastating the household. In response, Cameron set up her camera in the bedroom and took four post-mortem images of the child which she called ‘the sacred and lovely remains’. Cameron had previously taken images of mock-death, such as The Shunamite Woman and her Dead Son (1865) and popular fictional ‘dying women’ such as the May Queen, Ophelia and Arthurian heroine Elaine. Unlike her other images, Cameron never offered these photographs for sale, but gave them as memento mori gifts to friends and family.

5. Cameron’s last word was ‘Beautiful.’ Cameron and her husband returned to Ceylon in 1875 to be closer to her sons who were managing their coffee plantations. She spent her remaining couple of years taking photographs of the women who worked on the estate and was visited by the painter Marianne North in 1877. Cameron returned to Freshwater for one final visit to her friends and family in the summer of 1878 but the strain of travelling proved too much. She was taken ill on her return to Ceylon, while staying with her son in the Dikoya Valley. She asked for her sickbed to be moved to the balcony so she could see the night sky. She whispered ‘Beautiful’, her final word, and died. Her son wrote to the family, ‘No death could be more calm, more beautiful than this.’