It’s Saturday morning and the kitchen looks like a bomb has exploded. I don’t mind though, I’ve got at least three more hours of Body of Proof to get through and I’ve been looking for an excuse to escape from my family to find out what happens next.

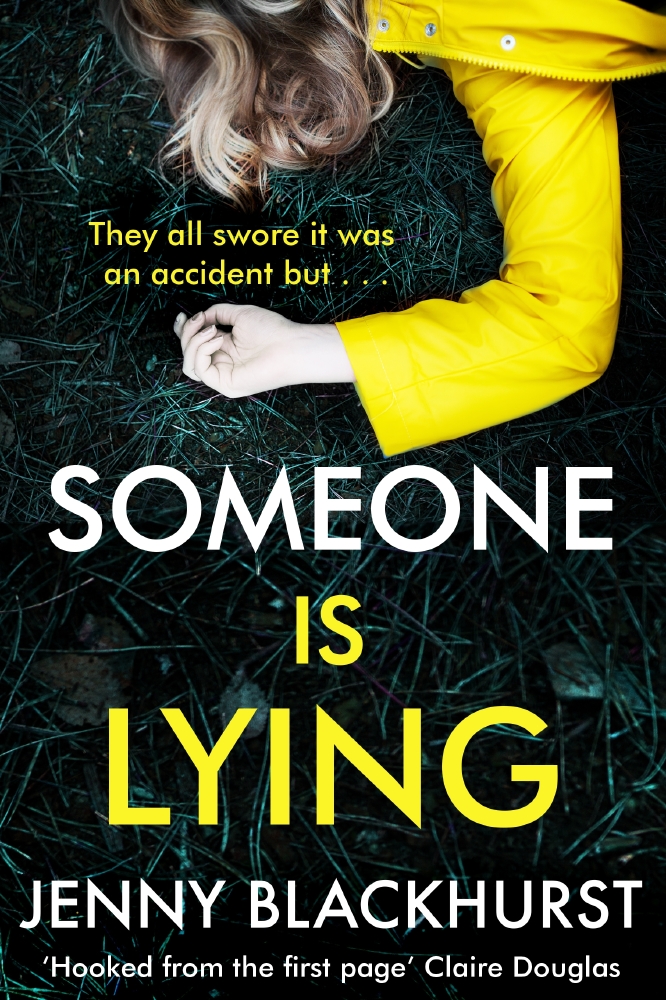

Someone is Lying

I hadn’t heard about the disappearance of Suzanne Pilley until a few days earlier, yet all of a sudden I was desperate to know what clues would emerge while I loaded the dishwasher. As I cleaned I analysed each new piece of information – how did that fit with what I’d found out yesterday? Not only did I have access to information that was never made public in 2010 but now I could check distances on Google Maps, I could see for myself the route that David Gilroy took as he allegedly disposed of this poor woman’s body on his way to a meeting and the discrepancy between how long it took and how long it should have taken. Now I wasn’t just reading about the investigation – I was part of it.

We have always been fascinated with crime and punishment. Finding the culprit, apportioning blame then seeing retribution meted out helps us make sense of senseless acts like murder. Now though, with the absolute wealth of information available 24/7 our interest can extend to obsession. We discuss cases on Reddit, certain that we have come up with theories that the police missed – such is the greatness of our deduction skills. ‘Unnamed suspects’ are tracked down in minutes via Facebook profiles. The first thing that happens when there is a newsworthy crime is that social media explodes with ‘something doesn’t feel right here’. We want to be the ones who slot the clues together, to encourage others to look at the clues we’ve found and to validate our suspicions that there’s ‘more to this’ and that we could be the ones to figure out what really happened. Making a Murderer turned the world into armchair detectives, and the natural progression is to apply those detective skills to current news.

So what’s wrong with that? It’s human nature, isn’t it, to be curious? But while we are busy pointing out the inconsistencies in people’s stories and jumping to conclusions that feed our appetite for the salacious are we forgetting that there are real people behind every one of these ‘cases’? When fifteen-year-old Nora Quorin was tragically found dead in Malaysia there was an outpouring of sympathy on social media, quickly followed by armchair detectives determined that ‘something wasn’t quite right’ with the official story. These people didn’t stop to question how her parents must be feeling as they read those words, their determination to uncover a juicy mystery outweighed their humanity. How do Suzanne Pilley’s parents feel about my source of kitchen cleaning entertainment? One serious question about our fascination with uncovering the truth needs to be asked– is it truly worth it at the expense of the friends and relatives of the victims?

Someone is Lying by Jenny Blackhurst is out in paperback on 14th November 2019, priced £7.99 (Headline).