Recently I was asked to speak as part of a panel discussion about how AI is impacting creators whose copyright-protected works have been used to train AI models, often without their permission or fair pay. It was hosted by DACs, which is a not-for-profit visual artists’ rights management organisation, as part of the AI Fringe which was a series of events hosted across London and the UK to complement the UK Government’s AI Safety Summit, by bringing a broad and diverse range of voices into the conversation. The panel explored the challenges creators are now facing in protecting their IP rights, and how the creative and tech industries can work together to ensure a fair and just copyright landscape, as well as highlighting some of the more existential concerns creatives may feel about the growing capabilities of AI.

Lawrence Essex

Over the last year generative artificial intelligence has caused a stir in the creative industries, and in case you’re asking yourself what the hell that means, a generative AI is basically an application capable of learning patterns and structures from large quantities of training data to generate new data that has similar characteristics. Think of it like a vending machine, but instead of money you’re putting in a vast amount of information.

Many artists see AI as a threat to their craft while others see it as the dawn of a new age and a democratisation of the arts. Personally, I sit somewhere in the middle. As a film maker I’ve found AIs like ChatGPT incredibly useful for demystifying the sort of long jargon used in funding applications, by asking it to explain things to me like I’m five. And I’ve used image generators like Midjourney to create images for pitch decks and even just bringing my stories to life for fun. In that sort of way, it can be a very powerful educational tool. And I think like any tool it has the capability to help build amazing things but also, in the wrong hands, wreak untold destruction.Earlier this year Sci-fi lit magazine Clarkesworld closed their submissions because they were inundated with short stories that had been written by AI. Author Jane Friedman had to deal with a unique case of identity theft, in which someone had used AI to pen a series of books under her name which they then self-published on Amazon, tricking people into thinking they were written by Friedman. Even just this week actress Scarlet Johansson has taken legal action against a company called Lisa AI for stealing not only her likeness but also her voice, featuring her in an ad (which has now been taken down) for the app, without her consent.Like Monstro the Whale swallows schools of fish, generative AIs like Midjourney and Stable Diffusion use data scraping tools, which collect vast quantities of images and corresponding text from the internet, and then uses that data to train itself. So, if you wanted to generate an image in the style of say, Frank Frazetta or Quentin Blake, then it would use examples of images listed with their name that it has learned as a basis to create a new image of what you asked for in their style. You could argue that all art is influenced by other art, but the companies behind these AIs didn’t obtain permission or offer compensation when using artists work in the models that train their AI. So now anyone could spit out image imitating an artist that has painstakingly honed their craft and individual style for years, in the blink of an eye and use it for almost anything. In fact Greg Rutkowski, a talented polish fantasy artist, became shorthand for users who wanted to generate high fantasy artwork featuring dragons and magical beings when Stable Diffusion launched last year. Which unsurprisingly negatively impacted his commissions and revenue.

In May of this year, members of the writer’s and Actor’s guilds of America went on strike, partly due to safeguards around scripts being written using AI and actors’ likeness being used without their permission, as well as background actors being replaced entirely with AI generated models. Something that Disney tried recently in a film called Prom Pact, only to garner disgust and laughter from audiences at the horrifying dead eyed uncanny valley nightmare creatures crudely mimicking human behaviour like some kind of early prototype Terminator, before Cyberdyne systems managed to make the T-800 look like human Schwarzenegger. But more than likely, eventually the technology will evolve, and become nearly indistinguishable from reality.

I think it’s this kind of use of the technology, that outright seeks to replace people to save a buck, that is giving people a genuine cause for concern. But as is often the case, I don’t believe the blame lies with AI itself, or the idea of it, but the human greed pulling at its strings. I think the biggest issue is that legislation will struggle to keep up with the quickly evolving technology. Afterall is a hammer or a saw inherently dangerous on their own? Not at all, they’re just inanimate objects, and in the right hands, once the wave of get rich quick schemers and scammers subside and the technology settles a bit and the right legislation is in place - and it remains to be seen whether or not some of these companies are sued to bankruptcy – but I think the coming times will (hopefully) give way to more a more ethical use of AI in the creative industries. Where it is simply a very powerful tool used to make the more administrative or technical processes less arduous and time consuming so that creators can focus on what they do best. One positive use case of AI I learned of recently would be the Artist Markos Kay, who In 2016 became disabled due to a chronic neuro-immune disease which has since rendered him largely bed-bound. He uses generative AI to help him continue to create art and illustrations, which are currently on display at Illusionary Canary Wharf as a part of his amazing sensory Latent Spaces exhibition.

So I don’t think it’s necessarily all doom and gloom, I remain cautiously optimistic. After all technology has always influenced the arts. It’s hard to say what exactly the long-term ramifications AI will have on the creative industry, let alone society. To quote Jeff Goldblum’s Dr Ian Malcom from Jurassic World, who was similarly speaking of the potential dangers of a landmark technological advancement, “Change is like death, you don’t know what it looks like until you’re standing at the gates.” The advent of photography saw a chorus of doomsayers proclaiming the obsolescence of painters, likewise cinema didn’t kill theatre, and despite the initial boom in use, CGI has not extinguished the art of practical effects. Nor am I convinced that AI will usurp humans entirely, after all the human experience is at the core of creativity. Since the dawn of our species, we’ve been storytellers, etching our experiences into walls, onto paper and now into machines. Storytelling is at the core of our history, our culture, and it births our future. We are dreamers, we conjure, we create, we craft, and life imitates art. A machine can only imitate what has come before, we’ll at least for now. And should the day arrive where AI begins to pioneer its own thoughts, well, I think we’ll have much bigger and more existential problems than fighting for fair usage and fair compensation.

The Book

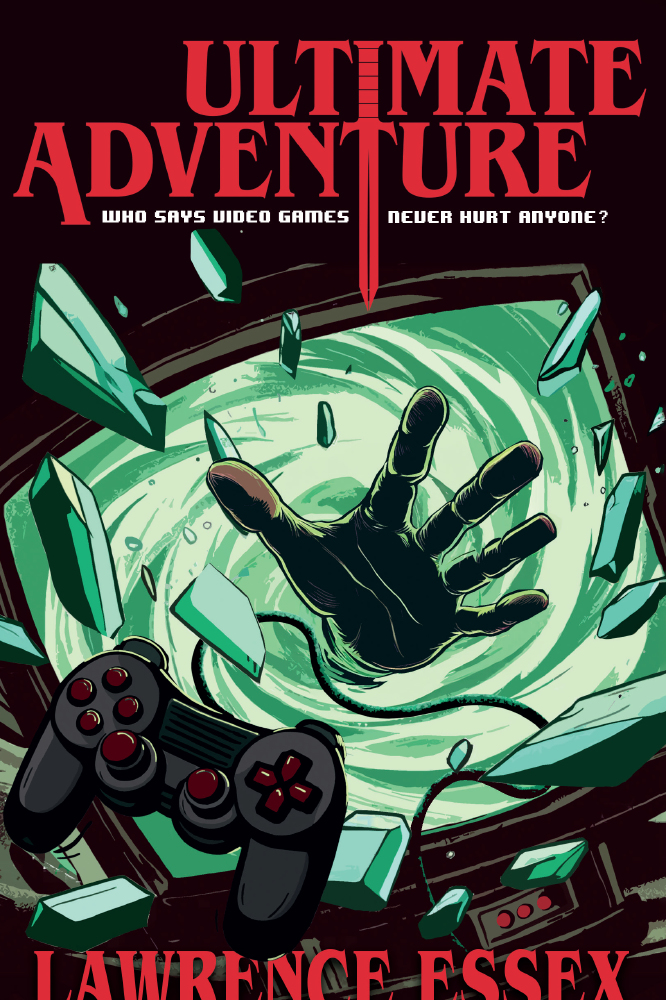

Lawrence Essex's Latest novel The Ultimate Adventure Who says video games never hurt anyone? is out now. Paperback £10.99 Available via Amazon and to order in all good bookshops.

Remy Winters has hit rock bottom: unemployed and living back home with her dysfunctional family. However, when she decides to immerse herself in the remake of her favourite childhood video game, the fantasy RPG Ultimate Adventure VII, she’s granted a great deal more escapism than she bargained for.

Finding herself trapped inside the game’s world, fantasy quickly spirals into a nightmare and she soon learns the game has some serious life – and death – consequences. Remy must assemble a party of real-world players and in-game companions to battle against walking corpses, hordes of monsters and, worst of all, the game’s primary antagonist – The Dread Knight Grimoirh.

If Remy wants to avoid a permanent Game Over, she’ll have to find three all-powerful crystal shards before Grimoirh does (sounds simple) and figure out a way home (bit harder) without breaking reality (she’s doomed).

Who said video games never hurt anyone?

Author Bio

Lawrence Essex is a writer, filmmaker and geek from Hertfordshire, England. His short films have aired on TV and at festivals such as Raindance and the British Urban Film Festival.

With experience shooting in stunning locations worldwide, Lawrence loves to escape reality and immerse himself in fantasy and roleplaying games, which was the inspiration behind his debut novel, Ultimate Adventure.

Tagged in author facts