Athens of the fifth century BCE was a city of contradictions. It was the foremost city of the Eastern Mediterranean, the cradle of democracy where some of the first scholarly history and philosophy was written, home to dramatists such as Sophocles and Euripides whose work is still performed, where the Parthenon and the Areopagus still attract millions of visitors annually.

Yet the wealth of the city was based on forced contributions from subject states and the work of slaves chained underground in the silver mines for all their short lives. The rights to vote and hold public office were confined to male citizens, a small minority, perhaps a fifth of the population, who met in the Assembly, the key decision-making body. Immigrants were heavily taxed and treated with contempt.

Athens was a divided society. Demosthenes, the eminent lawyer and politician, summed up (men’s) attitudes to women in a much-quoted speech:

“We keep sex-workers for the sake of pleasure, females slaves for our daily care and wives to give us legitimate children and to be the guardians of our household.”

Women had virtually no rights and, in families that could afford it, were hidden away in the home. If they went out they would wear head scarves and veils. And run their errands to the temple or the market as unobtrusively as possible.

Pericles the leading politician of the golden age, and Aspasia’s lover, remarked in his most famous speech, the Funeral Oration of 429 BCE:

“It is the greatest glory for a woman never to be talked about for good or for evil among men.”

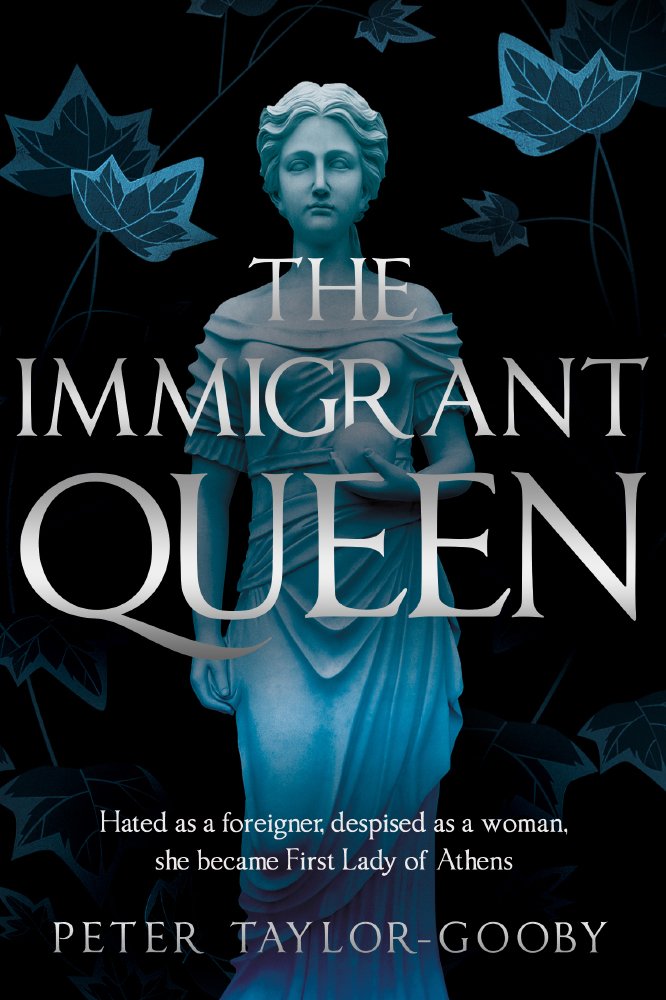

This was the city to which Aspasia, the leading character of my novel The Immigrant Queen, came as an immigrant and a woman, a person of no importance and where, against all the odds, she triumphed. It is striking that we know the names of many thousand Athenian men, but of only a few hundred women and then mainly as wives or mothers, but we know of Aspasia as an intellectual and as a beautiful and cultivated woman.

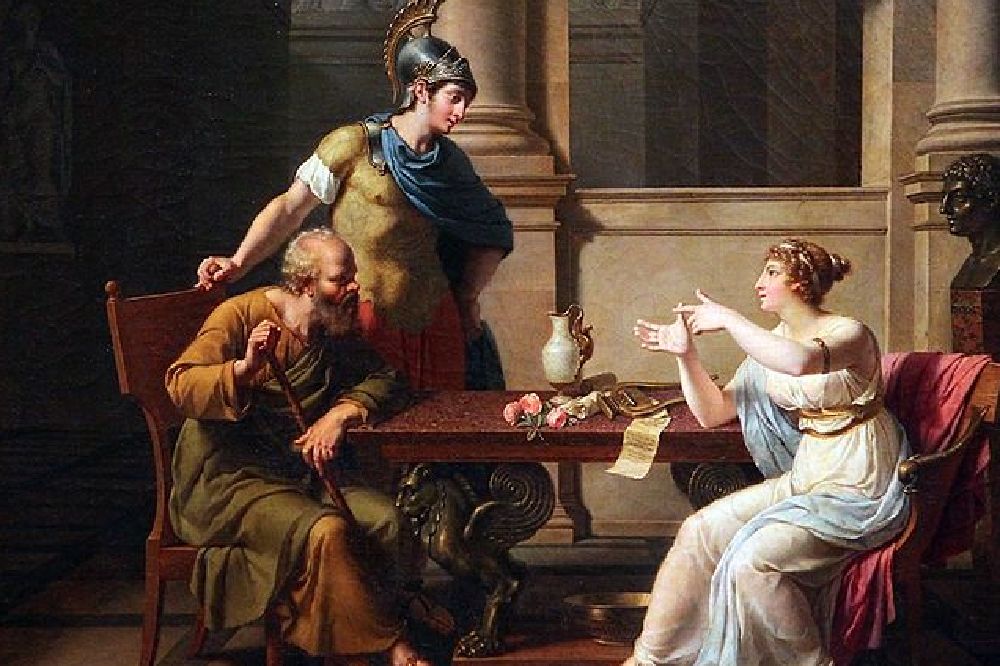

Athens was famed for its philosophy. The work of Plato and Aristotle is still taught and debated in our universities. Aspasia probably started as a sex-worker, yet she became the only Athenian woman philosopher of whom we know. Her works were quoted with approval by leading writers but we only have a few lines from them since no-one in the great library of Alexandria thought fit to copy them out. In Plato’s dialogue, the Menexenus, Socrates credits her with teaching him how to debate.

The fragments we have include examples of the “Inductio” a tactic which Socrates frequently uses to convince his interlocuter to change their views. It works by leading the other to express their opinions on a range of increasingly similar topics until they realise that their original assertion was at variance with their own general framework of ideas and admit that Socrates has bested them.

Diotima in the Symposium, one of the most famous dialogues, is the only female figure mentioned in Plato’s work. Most scholars think she represents Aspasia. As a woman she does not have a speaking role but her ideas are relayed by Socrates and form the basis of the concept of “Platonic love” – spiritual as opposed to physical love – which was so influential in the Renaissance.

Yet this is a society in which school-children copied out the tag:

“A man who teaches a woman to write should know that he is providing poison to an asp.”

Many writers comment on the beauty of Aspasia. She attracted the love of Pericles, the leading citizen, and they made a happy marriage by all accounts. Her story throws into relief the inequalities and conflicts of Athenian society – one of the greatest world cities, but a society which almost entirely ignored the contribution of the women who made up over half of its population.

Peters latest book The Immigrant Queen An Extraordinary Woman Of Ancient Athens is out 28/11/2024 ISBN: 9781836280606 Price: £10.99

The Immigrant Queen follows Aspasia a trafficked sex-worker that became the lover of Pericles, before publishing her own philosophical works, becoming Athens most prominent female figure.

Tagged in author facts