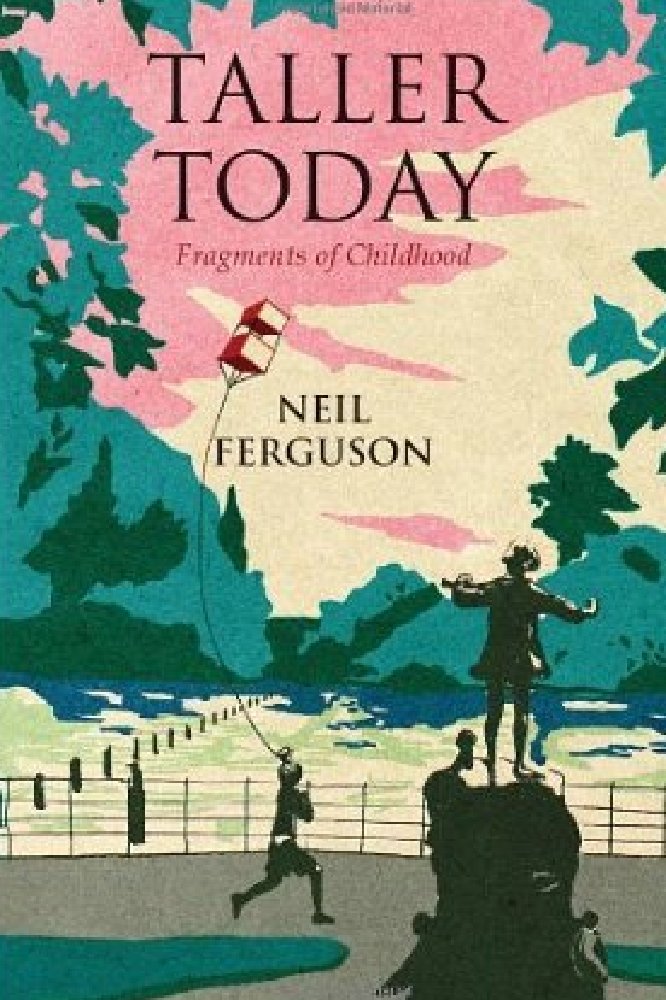

Taller Today

Taller Today is an account of my childhood up to the age of about fifteen, from around 1953 to 1963, from the Queen's Coronation to Please Please Me. To some extent it's also an account of my parent’s life in post War west London: Bayswater, Notting Hill, Shepherds Bush. It was a hand-to-mouth unsettled existence in the bad housing Alan Johnson writes about so nicely in This Boy – his streets neighbouring ours. It had some alarming twists and turns. Taller Today could be called a memoir, although I tended not to think of it as a memoir when I wrote it. Memoirs follow a certain formula. They can be very interesting, like This Boy, and you might feel sorry for the author. I didn't want the reader to feel sorry for the child in the book; I wanted to move her - and to do that I needed the tools of fiction: actual time, withheld information, metaphor, dialogue, juxtaposition, dramatic twists. I wanted, as far as possible, to give the first person narrator a naïve point of view, rather than to look back on him with the benefit of hindsight, as in a conventional memoir. I tend to think of the book as a non-fiction coming of age novel. I wanted to write about the lost world of childhood and my relationship with the dashing heartless hero of that world, my father.

Why did you want to explore the relationship between your father through writing?

My father wasn't a bad man, although he was a very selfish one. He did what was convenient to himself – and his wife and children had to like it or lump it. He was born into a posh lowland Scottish family the year after Victoria died; he went to Osborne and Dartmouth and was at sea as midshipman at the very end of the First War and at sea below deck in the Second. He helped invent a weapon that proved devastating for enemy U-boats. He had lost his own father when he was four and both his elder brothers were dead in Flanders by 1916, so with no male role models he came into his money when he was twenty-five and carried on like one of those dreadful Bright Young Things in Evelyn Waugh's Vile Bodies. He spent his money and, by the time I knew him, he had become a design engineer. He was the stereotype of the mad inventor. But I always liked him. We largely got on. He was a great talker. When I look at his life I see he was just as much a victim of his circumstances as I was of his mistakes. They might fuck you up, your mum and dad, but it's important to be able to forgive them, not to get stuck in some kind of pointless blame game. You can only really mature after you have done that. I recorded some of his narratives when he was alive – obviously not after - and transcribed a couple of them verbatim into the book.

Can you give us a brief insight into your previous books?

When I was young and took loads of drugs I wanted to write like Philip K Dick, the US master of ontological science fiction. How could a person be sure he wasn't a Turing machine? Dick's novels were funny, edgy, paranoid and unliterary; they explored political and metaphysical themes in worlds that were dominated by monopolistic corporations and authoritarian governments. Philip Dick's books were cheaply produced paperbacks with garishly illustrated inter-galactic covers that were located downstairs in the SF section of bookshops, next to children's books, a long way from Iris Murdoch and Margaret Drabble – later, Ian McEwan. I despised the English well-made novel. I wanted to be a paperback writer, as in the Beatles song. So I wrote Double Helix Fall, of which the critic John Clute said, 'This isn't Dick's best novel, but it is by no means one of his worst'. I travelled across the United States under my own steam and wrote a collection of short fictions called Bars of America, which is where the fictions take place. Dirty realism avant la lettre. I wrote a crime novel called Putting Out set in New York that has a semiologist detective, which is a satire on Style and Fashion and Semiology. My work became more serious as I did. My novel English Weather takes place over half a century through the eyes of eight characters who knew the central character, who has no point of view himself. The story is told backwards, from his death in prison to the moment he is taken away from his mother in Holloway. This last details is possibly informed by events that take place in Taller Today.

What was the lowest point in your childhood?

I don't remember my childhood having any low points. Children, then, did what they're told to do and shut up. I knew my mum loved me and that was all that mattered. Taller Today is not the most miserable Poor-Me story, I hope. Certain unfortunate events overtook me but they did not bring me down. I was too stupid to be brought down by them. You have to remember that children then came from another planet to grown-ups; their worlds did not coincide except at meal times. They weren't friends with each other, as I am with my own children. Taller Today stops just before the lowest point in my childhood because it's too painful to write about. When I was in the 6th Form at Holland Park School, doing my A levels, my dad got a job in Belgium so he upped sticks and took my mum to live there. My brother and sister had got married and left home, so I was parked in a B & B in Swiss Cottage. I was seventeen. I had no home to go home to. My parents had abandoned me again. I was utterly forlorn during this period and I had to wrestle with the Adversary, He who puts too easy questions on lonely roads.

What are your favourite reads?

The Great Triumvirate: Jane Austen, Flaubert, Chekov. Dickens, of course. Then, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, James Salter, JG Farrell, Philip K Dick, Pat Highsmith, JG Ballard, Jennifer Egan. Scott Fitzgerald's tiny masterpiece. I love Molly Kean's Good Behaviour. At the moment I'm re-reading Anna Karenina in Pevear and Volokhonsky's translation. I seem to get more pleasure in re-reading these days.

You teach Novel Writing at the City Literary Institute in London. How much does this affect your own work?

To parody the first line of Anna Karenina, All student novels are alike; each good novel is good in its own way. The students who come to my course are keen and want to learn but they nearly all tend to bring the same clichés about what a novel is supposed to be. I suppose, having taught my course for ten years now, I know all the mistakes a writer can make. My students' work is like a negative of how it should be done. As long as I bear that in mind, I have a chance of producing good work.

What advice do you give your students when they are starting out?

Why does everyone want to write a novel? I'll tell you: because everyone has a computer. When I started writing, novels were written on typewriters (or longhand) – no word processing, cut and paste, spellcheck or Wikipedia. You had to paginate by hand afterwards – and, then, how can you add an extra page? With a computer you can produce a manuscript at the press of a single key. I wrote my first two books on a beautiful 1935 Remington Portable – there's a nice picture of it in Taller Today with the bare-chested author looking handsome in Arizona in 1984. I tell my students how hard writing is. I do everything I can to put them off from continuing with their project. I tell them if they aren't interested in punctuation and grammar, if they're not interested in language, they might as well forget it. I tell them it takes 10,000 hours to master a difficult skill to a professional level, such as playing the cello, tennis, practicing medicine. They think I'm joking. I tell them to write about the world – things, places, people, dialogue – and not to witter about their characters' thoughts and feelings. Other people's thoughts and feelings are not really interesting to the reader. What the reader cares about are her own thoughts and feelings. I tell my students to leave enough room in their novels for the reader to make up her own mind. I tell them loads of things. The course prospectus bears the health warning: No faint hearts, please.

You are a poet as well as a novelist, so what can you tell us about writing in this form?

I write poetry now and then but I would never call myself a poet. I wouldn't dare. A poet is someone whose job description is to write the stuff every day. Anyway, my work tends to be out of kilter with what is accepted as poetry these days: self-referential, anecdotal, stripped of all aspects of skill that make it something difficult to do – rime, reason, rhythm, form – so that it might just as well be a piece of chopped up prose and often is. My taste in poetry - Auden, Larkin, the Italian Eugenio Montale – says everything about my feelings on the subject. I admire only a few poets, but our Poet Laureate, the Blessed Carol Anne, is one of them.

What is next for you?

Thank you for asking. I have two novels in the pipe line, both dramas (love stories, too, of course) located in a particular historical and political context. One set in the US embassy in Vichy, France (1940-43) where the misguided US State Department thought they could manage Petain's collaborationist pro-German government - quite the opposite, in fact, to the accepted view, which is of Claude Raine throwing the bottle of Vichy water into the trash bin at the end of Casablanca. The other is a low-life crime novel set in the period between the fifties and the Profumo Scandal in west London, my old stamping ground. Young working-class soldiers are getting shot in Aden to protect the oil route for the government. Sound familiar?

© Neil Ferguson Paris July 2013

Neil Ferguson is the author of Taller Today, published by Telegram Books; RRP £14.99